Quest Diagnostics Lyme Disease Test: A Look Under the Hood

When you send a sample in to Quest Diagnostics to test for Lyme disease, what happens? What are we looking for, and how do we know we’ve found it? In this article, we explain the test—actually two tests—and discuss what your results mean. We’ll also discuss when not to test, and look at one other test that can provide still more information about your patient’s Lyme disease.

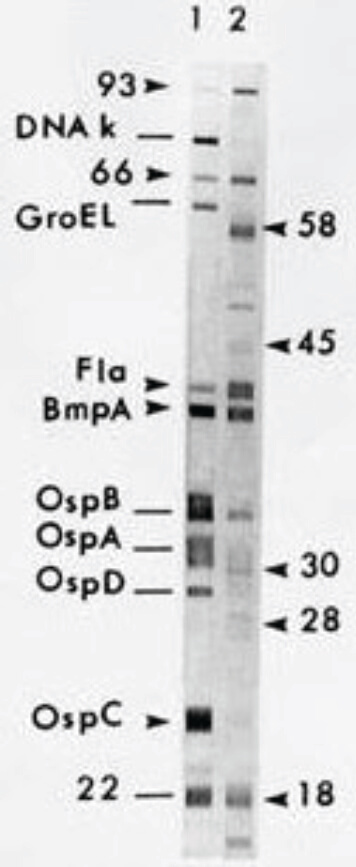

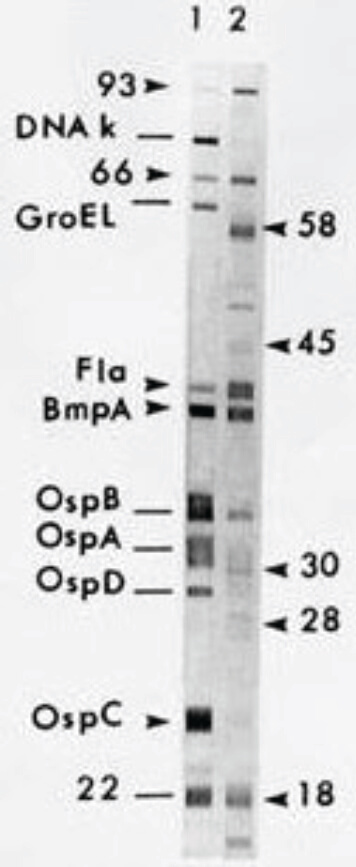

Positive Western blotThe Quest Lyme disease test is a two-step process. This is the process recommended by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention to test for Lyme, and is the standard for the accurate diagnosis of the disease. Both steps test for the presence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. Both steps use the same blood sample, so your patient doesn’t need to be drawn twice.The first step is a screening test, using an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) to look for the presence of anti-Borrelia antibodies. In this test, bacterial antigens coating the test plate are used as “bait” for the patient’s antibodies. Antibodies that bind to the antigen are in turn bound by a second antibody that is linked to an enzyme. That enzyme catalyzes a reaction that causes a color change; the intensity of the color is proportional to the amount of patient antibody captured on the test plate.“A negative result on the ELISA is confirmation that the patient does not have Lyme disease,” says Robert Jones, MD, Medical Director for Infectious Diseases at Quest Diagnostics. A positive result, however, is not definitely evidence of Lyme disease, for several reasons, and so must be followed up by the second test, a Western blot or immunoblot. “The Western blot defines whether the test result is truly positive.” As recommended by CDC, any sample testing positive on the screening test is automatically tested using the Western blot test.The Western blot test begins by separating multiple bacterial antigens using gel electrophoresis. It is these antigens that, during an infection, trigger the production of antibodies in the patient. Thus, when the patient’s serum is exposed to the gel, the anti-Borrelia antibodies within it will bind to the antigens. These can then be detected as a series of bands corresponding to how the antigens separated in the gel.Two types of patient antibodies are detected in the test. IgM antibodies reflect a relatively recent infection, while IgG antibodies are a sign of an older infection. “IgM antibodies typically disappear after eight weeks post-exposure,” Dr. Jones says, “while IgG remains in the serum for a very long time.”

Robert S Jones, DO MS FIDSA | Quest Diagnostics.Medical Director, Infectious Diseases“In the Western blot, there are three bands for IgM, and 10 bands for IgG. You need to have 2 out of 3 for a positive IgM result, or 5 out of 10 for IgG. Either one confirms the diagnosis,” he says.As these facts suggest, the timing of the test in relation to the putative infection is critical for obtaining meaningful results. “Patients may develop symptoms within several days of a tick bite,” Dr. Jones notes, but antibodies will not develop to a high enough level to be detected for up to several weeks. Samples obtained before that may give an equivocal, or even false negative result. The CDC recommends that in the case of patients with signs and symptoms consistent with Lyme disease whose screening test results are negative, a second sample taken after 30 days should be considered.Testing of patients whose medical history includes a previous bout with Lyme disease is also likely to give unhelpful results, this time a false positive. “You can do the test, but it doesn’t really have value,” Dr. Jones says. “The IgG is still likely to be positive from the last time they had it, and there may not be new IgM production.” In that case, the diagnosis relies on signs, symptoms, exposure, and geography.Quest also offers direct testing for the Borrelia bacterium in body fluids, using polymerase chain reaction to identify its DNA. However, Dr. Jones says, testing blood is not a high-return option, since the organism must be present, and the bacteremia is usually transient. “PCR is probably more usefully performed on joint fluid or CSF,” he says. “If a patient ends up in an orthopedic surgeon’s office with joint effusion, and the physician is sending off the joint fluid for other tests, PCR for Borrelia as well may be appropriate.”Finally, Dr. Jones said, it’s important to remember that ticks carry multiple pathogenic microbes, and that a negative result on the Lyme test doesn’t mean the patient doesn’t have any infectious disease. Anaplasmosis (caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum), babesiosis (caused by the Babesia parasite), and ehrlichiosis (caused by several species of Ehrlichia bacteria) are all spread by deer ticks, and a patient with a tick bite may have any one, or more than one, of these, along with or instead of Lyme disease.

Positive Western blotThe Quest Lyme disease test is a two-step process. This is the process recommended by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention to test for Lyme, and is the standard for the accurate diagnosis of the disease. Both steps test for the presence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. Both steps use the same blood sample, so your patient doesn’t need to be drawn twice.The first step is a screening test, using an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) to look for the presence of anti-Borrelia antibodies. In this test, bacterial antigens coating the test plate are used as “bait” for the patient’s antibodies. Antibodies that bind to the antigen are in turn bound by a second antibody that is linked to an enzyme. That enzyme catalyzes a reaction that causes a color change; the intensity of the color is proportional to the amount of patient antibody captured on the test plate.“A negative result on the ELISA is confirmation that the patient does not have Lyme disease,” says Robert Jones, MD, Medical Director for Infectious Diseases at Quest Diagnostics. A positive result, however, is not definitely evidence of Lyme disease, for several reasons, and so must be followed up by the second test, a Western blot or immunoblot. “The Western blot defines whether the test result is truly positive.” As recommended by CDC, any sample testing positive on the screening test is automatically tested using the Western blot test.The Western blot test begins by separating multiple bacterial antigens using gel electrophoresis. It is these antigens that, during an infection, trigger the production of antibodies in the patient. Thus, when the patient’s serum is exposed to the gel, the anti-Borrelia antibodies within it will bind to the antigens. These can then be detected as a series of bands corresponding to how the antigens separated in the gel.Two types of patient antibodies are detected in the test. IgM antibodies reflect a relatively recent infection, while IgG antibodies are a sign of an older infection. “IgM antibodies typically disappear after eight weeks post-exposure,” Dr. Jones says, “while IgG remains in the serum for a very long time.”

Robert S Jones, DO MS FIDSA | Quest Diagnostics.Medical Director, Infectious Diseases“In the Western blot, there are three bands for IgM, and 10 bands for IgG. You need to have 2 out of 3 for a positive IgM result, or 5 out of 10 for IgG. Either one confirms the diagnosis,” he says.As these facts suggest, the timing of the test in relation to the putative infection is critical for obtaining meaningful results. “Patients may develop symptoms within several days of a tick bite,” Dr. Jones notes, but antibodies will not develop to a high enough level to be detected for up to several weeks. Samples obtained before that may give an equivocal, or even false negative result. The CDC recommends that in the case of patients with signs and symptoms consistent with Lyme disease whose screening test results are negative, a second sample taken after 30 days should be considered.Testing of patients whose medical history includes a previous bout with Lyme disease is also likely to give unhelpful results, this time a false positive. “You can do the test, but it doesn’t really have value,” Dr. Jones says. “The IgG is still likely to be positive from the last time they had it, and there may not be new IgM production.” In that case, the diagnosis relies on signs, symptoms, exposure, and geography.Quest also offers direct testing for the Borrelia bacterium in body fluids, using polymerase chain reaction to identify its DNA. However, Dr. Jones says, testing blood is not a high-return option, since the organism must be present, and the bacteremia is usually transient. “PCR is probably more usefully performed on joint fluid or CSF,” he says. “If a patient ends up in an orthopedic surgeon’s office with joint effusion, and the physician is sending off the joint fluid for other tests, PCR for Borrelia as well may be appropriate.”Finally, Dr. Jones said, it’s important to remember that ticks carry multiple pathogenic microbes, and that a negative result on the Lyme test doesn’t mean the patient doesn’t have any infectious disease. Anaplasmosis (caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum), babesiosis (caused by the Babesia parasite), and ehrlichiosis (caused by several species of Ehrlichia bacteria) are all spread by deer ticks, and a patient with a tick bite may have any one, or more than one, of these, along with or instead of Lyme disease.

Buy your own lab tests

Shop online for a Lyme Disease Test - no doctor visit required for purchase